December 2021

Save the bees! Aphis mellifera, or more commonly the Western honey bee, are a tiny yet mighty and essential member of our planet’s ecosystem for many reasons. Their survival and ability to thrive are often overlooked by the people who may need them most, farmers. As someone who is studying agriculture and communications within agriculture, being able to advocate for bees and the farmers that they help is important to me because I know that bees play a critical role in agricultural production and that farmers are sometimes hard to persuade once they develop a practice that works for them and their operation. Bees not only pollinate crops across the country, bee pollination accounts for about $15 billion in added crop value. Honey, the most common product of bees, created a value of $339 million with 157 million pounds of honey in 2019 (FDA, 2018). The goal with my paper is to open conversations about how farmers can help the bees and provide information specifically for them, without being critical of agricultural practices and operations. As This serves as a contrast to many messages I have seen over my life time, which were quick to criticize farmers and their operations. Farmers and other agricultural operators already face heavy criticism from outside perspectives who may not fully understand what it takes to work on a farm, and why farmers do what they do; I want to be an inside voice that can connect bee advocates and “ag-vocates”.

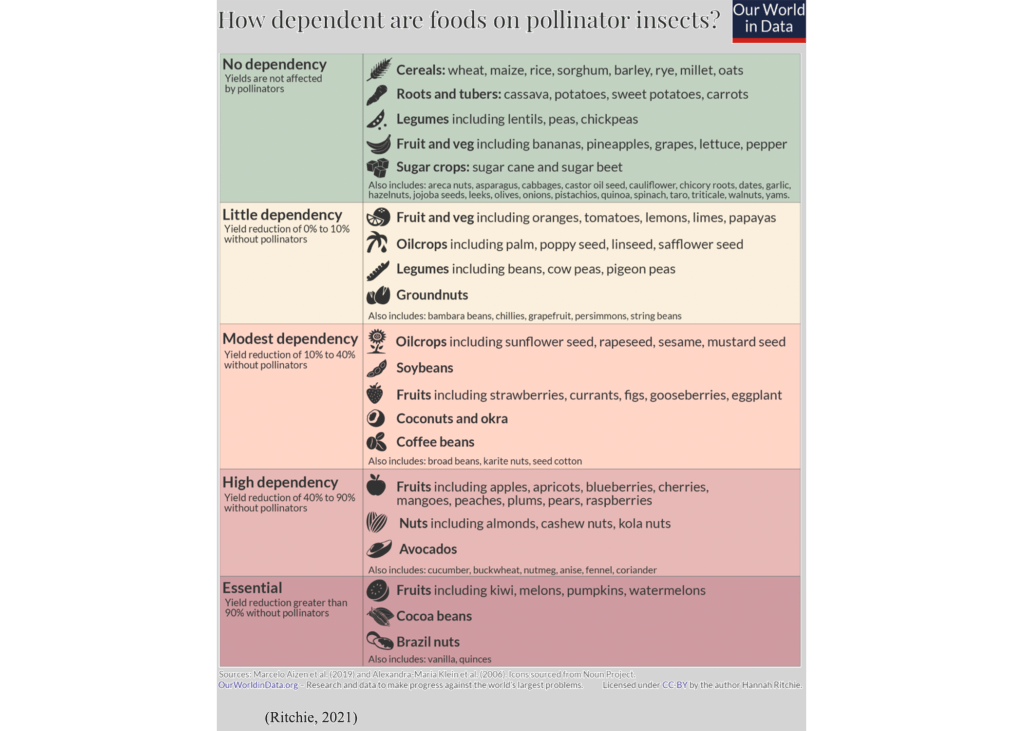

For centuries, humans have been interacting with bees with documentation from religious scriptures, mythology, iconography, and even in the stars of cosmology. In Greece, bees are considered an emblem for immortality (Hung, 2018). In 19th century eastern America, Telling the Bees was a tradition amongst beekeepers who would verbally inform their bees of any major event, possibly as an omen of good luck (Hung, 2018). In agriculture, the Western honeybee ranks as the most frequent pollinators for crops globally, helping other animal pollinators pollinate around 88% of all flowering plants (Hung, 2018). Of the 55 bee species managed by humans, a mere 12 species are specialized for crop pollination. Moreover, bees visit more than 90% of the world’s top 100 crops. (Patel, 2021). American crops such apples, cranberries, melons, almonds, broccoli, cherries, and blueberries all had yield reductions up to 90% without animal pollinators such as the Western honeybee (Ritchie, 2021).

However, decline of managed bee colonies and bee populations poses a major threat to our symbiotic relationships with bees. For farmers, the loss of bees is another added labor, as they will have to pollinate their crops by hand, as many farmers have already resorted to. According to bee specialist, Dave Goulson, of the University of Sussex, people are “rather rubbish” as pollinating, as it can be very hard for humans and a paintbrush to correctly pollinate the stigma of the flower, which can create a dangerously low production yield (Deutsche, 2021). As a response to this, Goulson recommends cultivating patches of wildflowers so that bees can feed while crops are not in bloom. In fact, many European and North American farmers have already adopted this idea, planning strips of flowers along the edges of their fields to help conserve bee populations. He, along with many other bee specialists, also recommends a limited use of pesticides in crops (Deutsche, 2021).

As farmers potentially spray their crops or plant chemical coated seeds, bees get exposed to pesticide residues through plant pollen and nectar, a sugary liquid produced by plants. The surrounding the water that is also contaminated by pesticides. The spray can drift onto the bees and outside the crop, and it can cause exposure as the plant uptakes the herbicide and carries it onto the bee with its stigma and/or anthers (Sanchez, 2016). While pesticides target animal pests, which would inevitably poison bees, the use of herbicides limits flower diversity, which can also have a negative effect on bee colonies and hamper their productivity (Sanchez, 2016). Certain weeds may be invasive and destructive to crops, but others can benefit the surrounding bee populations without destroying the crop. Moreover, the combination of agrochemicals in crops harms bees even more than if one chemical was used (Sanchez, 2016). As agrochemicals and insecticides are sprayed over crops, the singular droplets land on nearby bees and can be concentrated enough to kill them (Sanchez 2016). Even seeds that are treated are found to increase bee mortality as well. Alternatively, the use of granular pesticides that are incorporated into the soil are found to have no direct exposure to bees (Sanchez, 2016). The use of agrochemicals has significantly shifted the way beekeepers manage their hive. The shift to quality pollen over quantitative pollen has made it even harder for beekeepers to effectively manage their colonies. As the forager bees collect contaminated pollen and return it to the queen and larvae, the whole colony is eventually exposed and experiencing similar ill-reactions such as ragged wings and lethargic behavior, a tongue hanging out is a sign of poisoning (Sanchez, 2016).

Bees also rely on biodiversity to remain productive and thrive in their environments. Within the last 50 years, food demand has risen with global population and agriculture has transformed onto an industrial platform, leaving less and less wild land that flourishes with native biodiversity to fight food insecurity. To combat this, researchers recommend incentives for farmers that work to restore pollinator-friendly land by adopting agroecological production methods alongside their operations and taking extreme caution in choosing what time and method of applying agrochemicals (Nicholls, 2013).

Agroecology is sustainable farming that aims to work with the land as it naturally is. Agroecological production relies on the natural features of the native land and can amplify any agricultural operation (Misachi, 2017). Increasing plant diversity and soil cover by intercropping or planting more than one crop on the same piece of land (Misachi, 2017). Methods of intercropping can be applied on the industrial level when different crops are planted in alternating strips and still allowing room for machinery, called strip intercropping (Misachi, 2017). On the smaller level, diverse plants can be mixed and bunched naturally, but orderly. On a more complicated level, one crop can be planted and flower/develop, and the next crop planted right before harvest of the first crop with a method called relay intercropping (Misachi, 2017). Intercropping not only amplifies biodiversity, which is essential for bees to thrive, but it can also be a tool to increase income and energy with less land. Intercropping is shown to increase incomes by 33% and land output by 38%, as farmers are maximizing the potential of the land they are on (Martin, 2018). Other practices can be much simpler, such as planting or seeding into untilled soil, which increases organic matter in the top five centimeters of the soil, which improves overall water filtration, development of microflora and microfauna, fertility, and structure (Martin, 2018).

Bee pollination also carries major economic value. Globally, animal (mainly bee) pollination improves crop quality, quantity, and economic output by $235-577 billion U.S. dollars annually (Khalifa, 2021). In Europe alone, around 10 % of the agricultural production economic value is possible mainly by bee pollination. In the United States, pollinators are well recognized for increased yield, fruit size, and income in three crops: cucumbers, cranberries, and pears (Khalifa, 2021). For apple producers in Argentina, as thriving colonies of bees visited their orchards, fruit set increased by 15% which led to a 70% increase in profits. Pear producers noticed their fruits were, on average, 20% heavier when they were visited by bee colonies (Geslin, 2017).

If honeybee populations continue to decline, and farmers lose physical or financial access to pollination services, researchers are concerned that agriculture and the food supply chain will suffer major disruptions (Breeze, 2016). Pollination is a major economic service that is also threatened by biodiversity and land loss (Breeze, 2016). Many producers are forced to rent beehives, which can be an extensive process for both the farmer and the beekeeper. For example, to transport the hive, the keepers rely on the cool night temperatures to deliver the bees because the bees don’t fly around as much (Breeze, 2016). If a farmer were to need pollinators, they would need to move the hives into the crop once some flowering as begun, to avoid potential favor over competing non-target plants. For farmers in areas with poor weather and few wild honeybees and/or produce an “unattractive” crop with many competing weeds, more beehives will be needed per acre (Breeze, 2016). The already recommended starting point is one hive per acre (UGA Honeybee Program, 2020). However, many growers will prefer to rent two hives per acre to account for bad weather days, with each hive costing about $45-$200 U.S. dollars, determined by type of crop, distance beekeeper must travel, and general wild honeybee availability. Farmers that need more hives will need to spend more money on something they can already preserve within their operation (Breeze, 2016).

Overall, the Western honeybee is an iconic symbol when we think of nature and serves as an important component to crop agriculture across the planet. Farmers can simply plant gardens of flowers for local bee colonies to collect from, which will help their own yield in return. My own grandmother recommends Lilac, Mint, Sunflowers, and Lavender. Without bees, many of the crops we cherish in American agriculture would struggle, if not cease, to exist. As always, save the bees!

Leave a comment